The Supreme Court’s Decision in Warhol v. Goldsmith and the Importance of Licensing

The long-awaited Supreme Court decision in Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc. v. Lynn Goldsmith, et al, was issued early yesterday. The majority opinion, written by Supreme Court Justice Sotomayor, maintains the traditional outlook on what constitutes “fair use” while stressing the importance of commercial licensing arrangements.

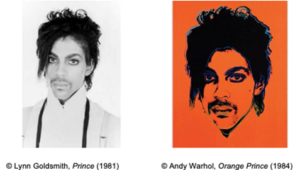

The case revolved around whether Warhol’s adaptation of a photograph taken by Goldsmith of the musical artist Prince infringed Goldsmith’s copyright rights or could be considered fair use. The original photograph and Warhol’s adaptation are shown here:

The key take-aways from the decision are:

- Andy Warhol’s Orange Prince was not entitled to the “fair use” defense because Warhol’s works served the same commercial purpose as Goldsmith’s photo: to be used as a feature in a magazine issue about Prince around the time of Prince’s passing.

- The Supreme Court did not comment on the copyright implications of Warhol’s other fifteen (15) works in the Warhol’s Prince Series.

- The Supreme Court did not directly opine on the Second Circuit’s narrower interpretation of what constitutes a “transformative” use of an original work.

- Instead, the Supreme Court recalled the importance of already existing factors when considering whether the nature or purpose of the new work favors a finding of fair use, particularly, whether the purpose or use is commercial or nonprofit and educational.

In its Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, The Andy Warhol Foundation (“AWF”) raised to the Supreme Court’s attention that the Second Circuit, “concluded that even where a new work indisputably conveys a distinct meaning or message, the work is not transformative if it ‘recognizabl[y] deriv[es] from, and retain[s] the essential elements of, its source material.’”[1] If this holding was affirmed by the Supreme Court it would arguably change, at a fundamental level, the fair use defense.

However, despite this opportunity to completely revamp the fair use defense, the Supreme Court kept its analysis quite narrow to the underlying facts of the case. Indeed, if anything, the Supreme Court refocused its analysis by keeping to the traditional fair use factors.

So, what is the “fair use” defense anyway?

“Fair use” is a defense to copyright infringement that, essentially, allows people to copy – without authorization – copyrighted works (or parts of copyrighted works) in certain circumstances. To determine whether a new work is entitled to the fair use defense, courts consider the following:

- the purpose and character of the use,

- the nature of the copyrighted work,

- the amount and substantiality of the work used, and

- the effect of the use on the potential market of the copyrighted work.

Under the first factor, if the purpose and character of the new work is transformative the court will typically find the new work qualifies for fair use. Generally, “transformative” has meant that the new use adds significant value or repurposes the original in a way that changes its meaning, message, or function. Traditionally, courts have also considered whether the “purpose and character of the use” is for commercial profit or for research, educational, or informational purposes, with higher scrutiny being applied where the use is for a commercial purpose.

Central to this case, is that in 1984 Goldsmith’s photograph was intentionally selected and licensed for Warhol to use for a one-time reference for his illustration of Prince. Vanity Fair paid Goldsmith $400 on behalf of Warhol for this limited license. At this time, Warhol also created 16 other adaptations of the photograph. After Prince passed away in 2016, Vanity Fair’s parent company, Condé Nast, reached out to AWF and selected one of the adaptations (known as Orange Prince) to reprint in a commemorative issue of the legendary musician. AWF granted Condé Nast that license for $10,000 without seeking any permission or license from Goldsmith.

When Goldsmith challenged AWF, AWF quickly brought this matter to court seeking a declaratory judgment that Warhol’s Orange Prince did not infringe Goldsmith’s Prince photograph pursuant to the fair use defense. The Southern District of New York agreed with AWF on summary judgment, only to be reversed by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals.

In the Second Circuit opinion, the Court emphasized that for the secondary work to be transformative, its “purpose and character must, at a bare minimum, comprise something more than the imposition of another artist’s style on the primary work…”[2]

The Supreme Court decided not to directly engage with the Second Circuit’s more narrowed definition of “transformative.” Instead, the Supreme Court reminded us that the first factor being, “the character and purpose” of the new use, is not solely decided by whether it is transformative. Rather, being transformative is only part of determining the first factor which must also be determined by whether the purpose of the secondary work is commercial in nature. Here, the Supreme Court found that “… AWF’s use is of a commercial nature. Even though Orange Prince adds new expression to Goldsmith’s photograph, in the context of the challenged use, the first fair factor still favors Goldsmith.”[3]

The Supreme Court’s opinion re-establishes important boundaries when considering whether the secondary work is transformative or simply infringes upon the original author’s right to make derivatives. Particularly, the new work “must go beyond that required to qualify as a derivative” of the original.[4]

Leading up to this decision, GS2Law held an Art Law Talk with acclaimed photographer Ernie Paniccioli on the potential implications presented by this case. Paniccioli opined that as a creative, the concerns on both sides are compelling, but nonetheless, it seems unfair that another artist could make a fortune based on the same work which the original photographer was only compensated nominal wages (if any). More about this Art Law Talk can be found here.

These sentiments, along with Goldsmith’s, dovetail with this week’s House Judiciary Subcommittee Hearing on Interoperability of AI and Copyright Law where “consent, credit, and compensation” were the hallmark words of the day.[5]

Considering that the Second Circuit decision remains good law, it will be important to keep an eye on how its more narrow interpretation of what is “transformative” will shape future decisions in this circuit. Nonetheless, whether any license arrangement exists will become a critical factor following this Supreme Court opinion.

[1] Petition for a Writ of Certiorari, Case No. 21-869 (Dec. 9, 2021).

[2] Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 11 F.4th 26, 42 (2d Cir. 2021).

[3] Andy Warhol Foundation for Visual Arts, Inc. v. Goldsmith, 2023 WL 3511534, at *8 (May 18, 2023) (emphasis added).

[4] Id. at *9.

[5] The Subcommittee on Courts, Intellectual Property, and the Internet, “Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: Part I – Interoperability of AI and Copyright Law,” Hearing (May 17, 2023), located at: https://judiciary.house.gov/committee-activity/hearings/artificial-intelligence-and-intellectual-property-part-i